Why The Movies Will Never Feel The Same Again

How the role of cinema has changed in the shifting media landscape and what it must do to survive. (Also vaguely an introduction to Media Ecology)

This essay was adapted from my video essay “Why The Movies Will Never Feel The Same Again” available on YouTube and Nebula without ads. I’m providing a written version because it will reach a different audience and is easier to reference or cite, but the video version contains a fair amount of archival footage and references that help support my narrative, so you may prefer to watch if you’re so inclined. As always I couldn’t do work like this without the support of my patrons and Newsletter subscribers:

I. The Exorcist Sparks Moral Panic

In 1973 David Sheehan went out to capture the audiences reactions to a movie that was becoming wildly popular. Reporting for KNXT-TV he said: "The manager of the National Theatre in Westwood says that there indeed are at least a dozen people who faint or become ill during every showing."

A hit that took Hollywood by surprise, The Exorcist quickly set box office records, becoming one of the first “Blockbusters” of the New Hollywood era. It also cause people to freak out.

There were reports of people screaming and running out of the theater, becoming ill and vomiting, being carried out of the theaters on stretchers. It incited a genuine moral panic with some religious groups believing the movie was causing demonic possessions.

None of this seemed to hurt its popularity (it probably helped it). Scalpers reportedly would sell tickets sometimes for hundreds of dollars. The movie ran in the theaters for two years. And its cultural impact has been lasting. A lot of people credit The Exorcist for playing a big role in starting up the satanic panic, something that was still going on 20 years later when I was born in the 90s.

But if you released this movie now, in 2025, what would happen?

It would probably do well at the box office, horror movies are still a good bet, and The Exorcist is a well constructed scary horror movie. But I don't think it's hard to argue that it wouldn't have anywhere near the same cultural impact. And this isn't just because culture has become less religious. Jaws, which was released just a few years later, inspired a similar kind of cultural panic. One that also had such a profound effect that to this day, some scientists call our collective irrational fixation on shark attacks (relative to other more dangerous things) “the Jaws effect.”

The reality is in the 2020s, Movies just don't have the same kind of cultural impact that they used to. Sure, people still might flock to the theater for a Minecraft movie or Barbenheimer, but they're being drawn in by massive marketing budgets and stories that draw from existing intellectual property. I could be wrong, but while Barbenheimer might have trended on Twitter and TikTok for a week, it doesn't seem like either movie will inspire a shift in mindset on Barbies or nuclear bombs that will echo through the culture for decades. At least not anywhere near the scale we saw with something like The Exorcist or Jaws.

A very common explanation for this is that movies just aren't as good. And sure, The Exorcist and Jaws are incredibly well-crafted films. Friedkin and Spielberg were basically at the top of their game technically. They knew how to wield all the forces of cinema that were available to them at that time for maximum effect. I will admit that in some ways, the major day-to-day fair at the box office is below the quality level of The Exorcist or Jaws, but there are still incredible major movies being made today and I don't think the shift in average quality is enough to really, truly explain the dramatic shift in cultural impact that has happened over the last 50 years. And ultimately even if you somehow could release The Exorcist for the first time today, it just wouldn't have the same impact. That means something else has changed. We've changed, the culture has changed, how we respond to the movies has changed. And I'm not saying going to the movies isn't fun anymore or has no value now. There are plenty of movies that provide cool, entertaining, even awe-inspiring experiences at the cinema. But on average, for me (and I gather for many others), it just doesn’t feel the same as it used to.

This essay is my attempt to explain this shift, and to do so we’ll have to dig into a media theory that I think is vital for truly understanding—not just the movies—but the shifting media landscape that we’re living through and some of the changes that are happening in our culture right now.

"You see, suddenly, if you've noticed, the mood of North America has changed very drastically." —Marshall McLuhan (1967)

II. “Phonevision”

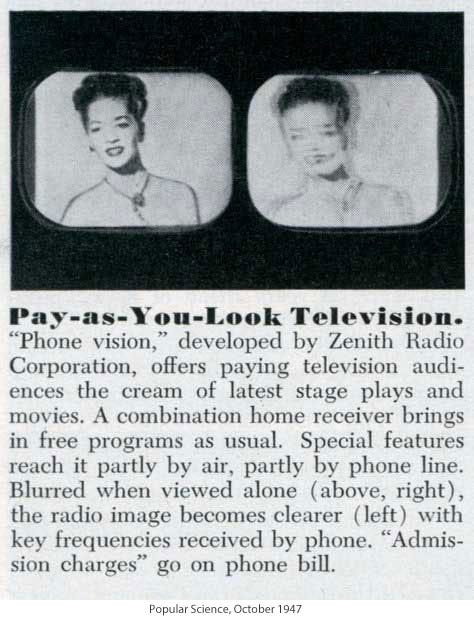

Chicago, January 6, 1951. The Zenith Radio Company begins testing an exciting new technology. If you’re one of 300 test households, for $1, you can order a movie directly to your home television set simply by sending a phone signal.

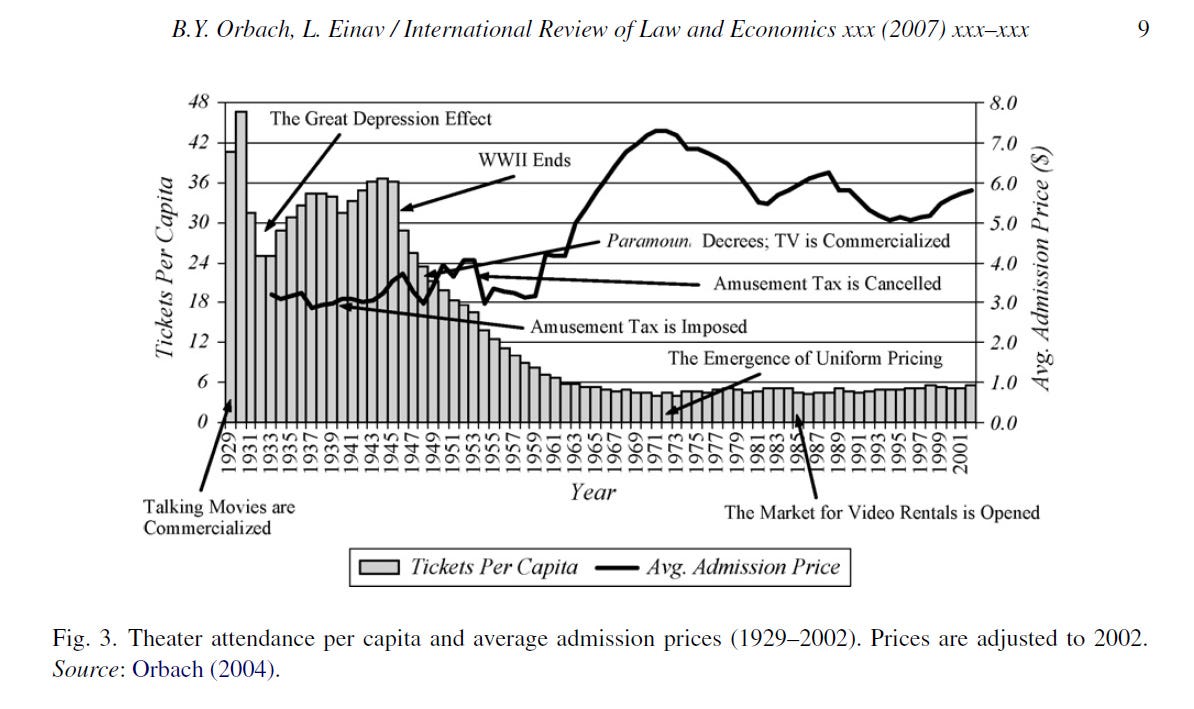

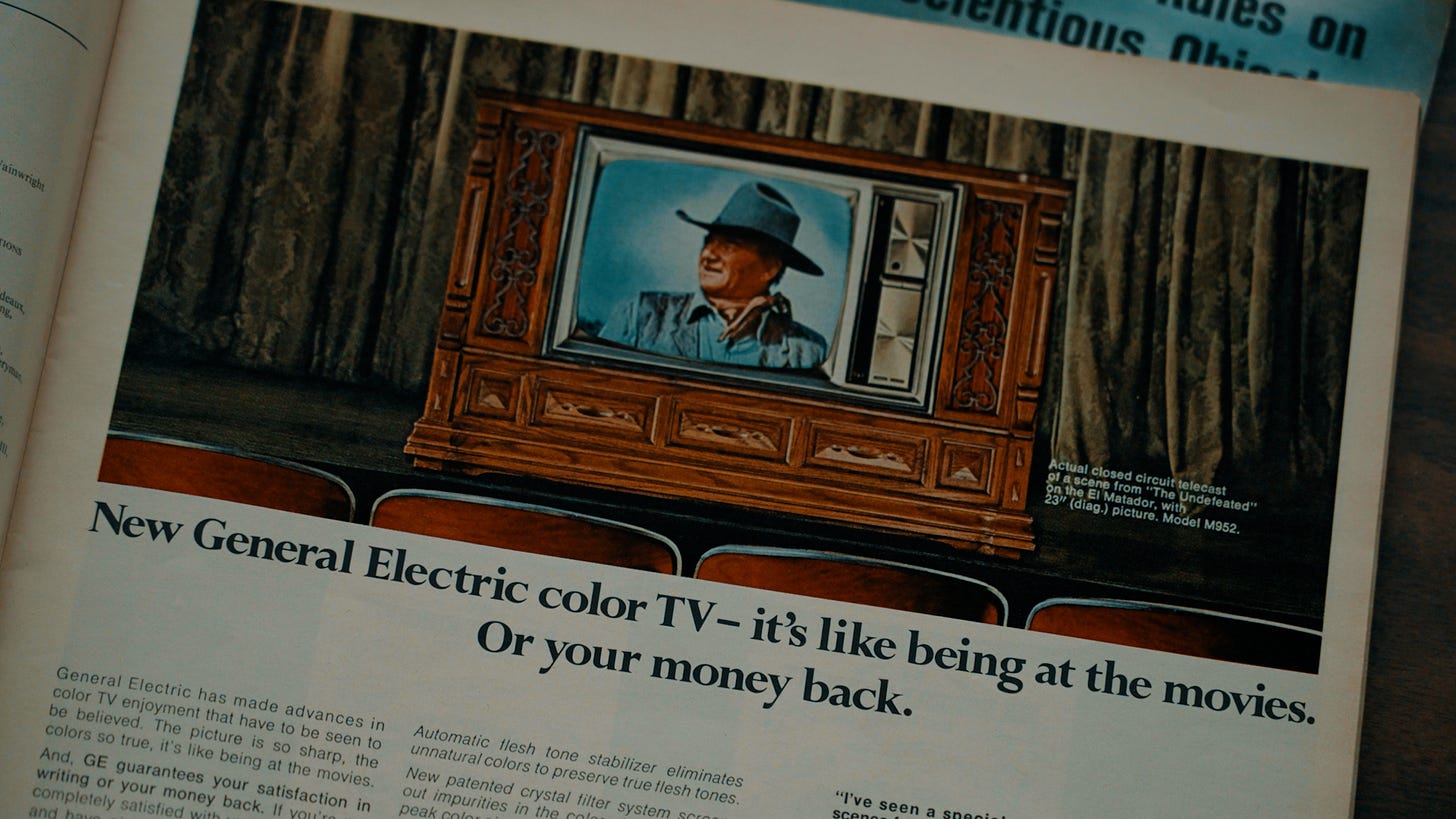

Seeing this, movie theaters and studios already feeling pressure from antitrust regulations and the rapid explosion of home television feared phone vision posed an existential threat. What will happen to the industry, they wondered, if movies can skip the theater and go straight to people's televisions at home? The industry pushed back, even lobbying the government to try to ban early pay-per-view movies. And while the technology didn't take off at the time, their fears were not unfounded. TV would not spell ultimate death for cinema, but by the 1950s, theater attendance was already in decline from its peak in the 30s and 40s.

It's hard to overstate just how big a deal movies were in the first half of the century. Theaters were a foundational American institution. In 1940, some reports indicate that over 60% of Americans were attending the cinema weekly, 20% more than were attending religious services each week.1 The cinema was a community gathering place. Small local neighborhood screens would show one movie at a time. The newsreels that ran before films were often the only opportunity citizens had to get a glimpse of the second world war as it unfolded abroad. This was the era of the Hollywood studio system with each of the big studios cranking out over a hundred movies each year.

But by the 50s, cinema attendance was in free fall. The Hollywood clergy and theater owners were panicking. Could cinema compete with the ease and convenience of the entertainment now available in the comfort of people's homes? Some in the industry attempted to ease their worries by recalling how Hollywood had already overcome significant threats. One exhibitor told Box Office Magazine it was "new and improved methods of presentation that had turned the tide in cinema's costly, discouraging, and prolonged fight against radio entertainment."2

TV shook the industry. And with antitrust regulations that made it so the studios couldn't own their own theaters anymore and other post-war cultural changes like suburbanization happening at the same time, by the 1970s, the number of theatrical admissions had fallen over 70%.

But the movies wouldn't go quietly. To try to win back audiences, theaters and the studios made the movies bigger and more exciting, implementing widescreen cinemascope, 3D, and better sound. Movies like Jaws, The Exorcist, and Star Wars found people lining up around the block. These new, bigger, bolder, blockbusters gave cinema attendance new life, and by the 80s, movie-going had stabilized, and with rising ticket prices, box office income was hitting all-time highs.

But even though this new world of multiplexes and blockbusters still had significant cultural influence, the movies and Hollywood had changed forever. They would never again represent the same thing to society that they had in their golden era.

In January 2007, just six days after Steve Jobs announced a technology that would shape the coming decades, a company that mailed DVDs to subscribers announced Watch Now, a service that would allow consumers to instantly watch a movie on their computer. These two technologies together would set in motion a transformation in how we consume media over the next decade, eventually sending the film and TV industry into the state of crisis it currently faces.

III. Hollywood In Crisis... Again

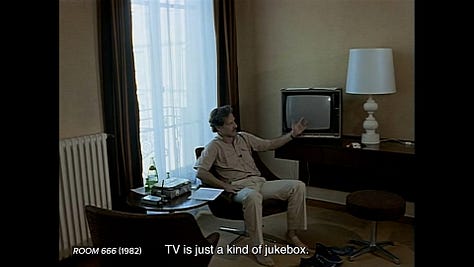

"‘Cinema. Is it a language about to get lost an art about to die?’ … It's obvious that it's on the way out."

-Paul Morrissey in Wim Wenders 1982 Documentary Room 666

Since cinema was born, basically every generation has been grappling with what it perceives to be the death of the medium. Almost every technological innovation has been perceived as a threat by cinema. Some of these like Television have proven to be credible—but others, like color filmmaking or home video, have proven to be false alarms, with theatrical attendance actually going up during those periods.

But in 2025, I think cinema truly does face the most credible set of challenges it has seen since the 1950s.

Like they did with TV, studios initially resisted streaming before eventually scrambling to join in. As streaming services like Netflix have grown into full-scale studios, and studios launched their own streaming platforms, it began a transformation in the economics of filmmaking that we're still in the midst of now. And when a global pandemic cratered the box office to all-time lows, the shift to streaming felt like a lifeline for the studios.

Theatrical windows have shortened, already down from the two years we saw with The Exorcist in the 70s to an average of 90 days in the 2010s—now we're down to just a few weeks, or in some cases, no exclusivity at all.

Consumers already burdened by lingering pandemic fears and economic pressure, combined with rising ticket prices, increasingly opt to wait for a streaming release.

There are reports claiming that Hollywood studio backlots, once the site of production for a global cultural force, have been sitting dormant. And in 2023, industry unions engaged in historic strikes to fight for fair compensation in the midst of these changes.

And yes, the movies themselves have been changing. I’ve documented their shift in philosophy towards metamodernism, but genre and subject matter has also changed significantly. As bigger budget narrative TV entered a golden era during the dawn of streaming, the stories that made up many of the mid-budget rom-coms, adult comedies, and dramas have moved to television.

This is how in 1980 you have a movie like Caddyshack for $6 million, in 1996 you have Happy Gilmore for $10 million, and then in 2025 you don't see any mid-budget sports comedies released in theaters. Instead you get a show like Stick from a computer and smartphone company, who likely spent much more than was spent on either of those movies on the show. A show written and produced by Jason Keller, who's worked almost entirely in film before this, and starring Owen Wilson, whose career also used to be entirely in film before it transitioned to television in just the last five years. And Happy Gilmore 2 comes out, but it goes straight to Netflix and skips the theaters entirely.

And that's just one small example of the many ways the lines between TV and film have blurred. The types of content you're traditionally used to seeing in a movie theater, and the types of content we call "TV" that exclusively streams at home in multiple parts, now often look very similar, are made by the same people using the same equipment, feature the same celebrities, and have similar budgets.

Over the last 20 years, while this transition has been happening, for most Americans the habit of going to the theater fell out of style. The American audiences stopped going to the movies and then deciding what to watch there. Instead, they began going to the movies to see a specific film. This change meant they needed to be convinced to attend the theater by a film's marketing. And facing more difficult challenges in drawing people to the theaters, the studio execs found that movies driven by recognizable intellectual property had built-in audiences that were much easier to market to. This is how remakes, reboots, sequels came to dominate the box office in the 2000s. By 2024, not a single one of the top 15 box office hits was an original film.

This paid off in the short run. Like the turn towards blockbuster filmmaking in the 1970s, the shift towards large IP driven franchises like the Marvel Cinematic Universe and the resuscitation of Star Wars has driven record-breaking box office receipts. Referring to these hits as "tentpole films," distributors, studios, even critics began to see IP driven megahits as the only thing holding up the industry, further pushing out smaller mid-budget offerings.

But this approach, which has worked relatively well in the 2010s, is starting to see diminishing returns in the 2020s. With almost no development of new original worlds, stories, ideas, IP, major blockbuster films have become a kind of cultural ouroboros. Cinema no longer creates the narratives that define the culture, instead it relies almost exclusively on its own past cultural influence or existing worlds, characters, and stories from other forms of media for its success.

All this while massive tech giants throw billions into developing technologies which threaten to undercut an entire workforce of craftspeople in the industry. Many fear AI tech will be too enticing for studios to pass up, even if it's not what audiences want.

Like in the 50s and 60s, cinema is now poised at a decisive moment. And just like cinema and its cultural influence changed significantly from the 40s to 70s, the movie industry that survives this current shift and its cultural influence will likely look radically different on the other side.

Those within the industry, and those paying attention to this, are already aware of pretty much everything I'm talking about here. There's been plenty of commentary going on about what's happening and how cinema might be able to weather this storm.

But this crisis is not the main focus of this essay. Its the backdrop. You might even say the crisis is a symptom of what I’ll be talking about. We're going to look at something underneath all of this industry crisis that has already quietly transformed what the movies mean to our culture. A shift not in the movies themselves and how they're made, but in the very way we perceive them. A change that has already happened, which may be irrevocable, but one which I think we need to understand if we want cinema to survive its current crisis and maintain cultural relevancy.

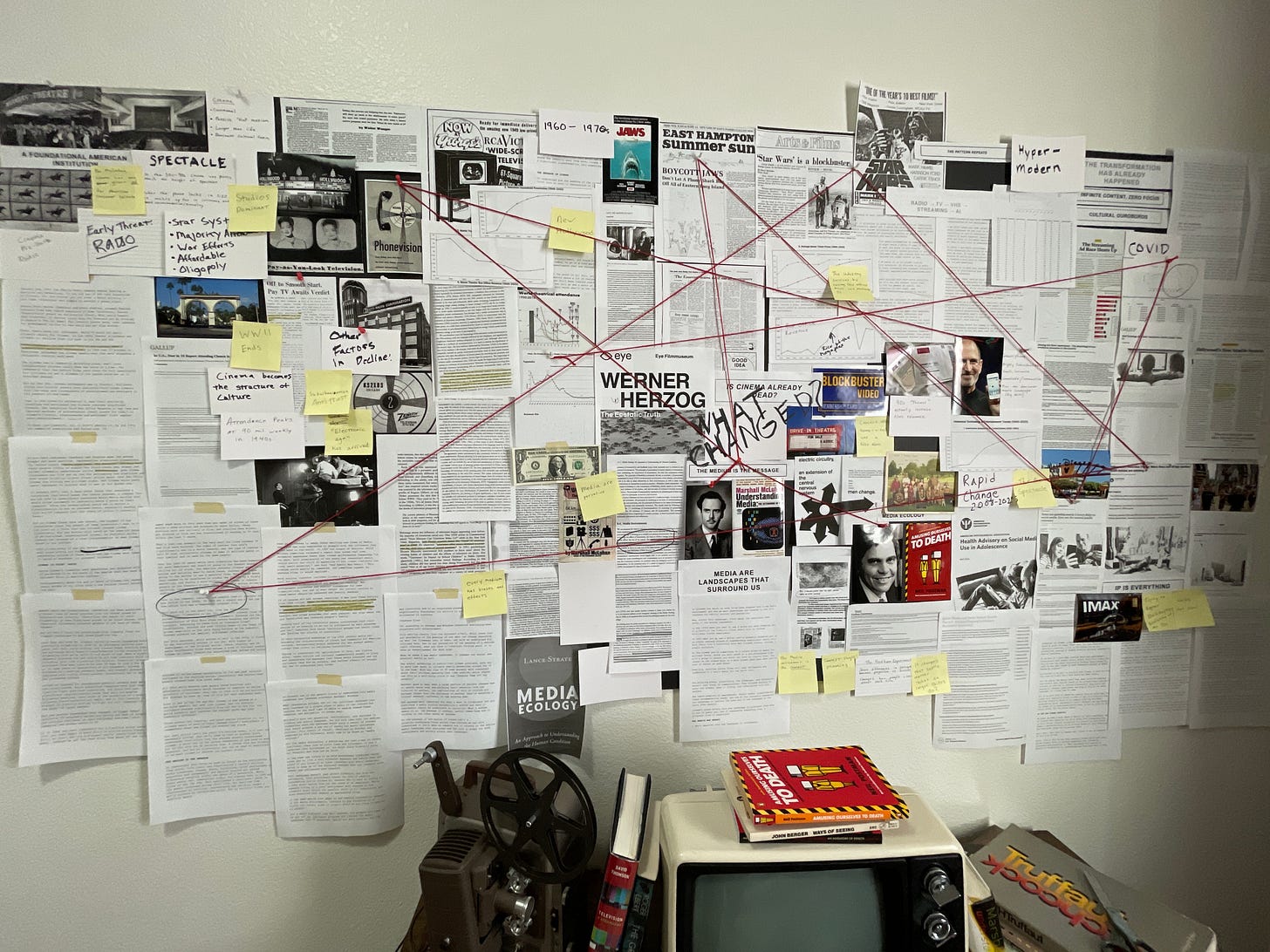

IV. What is Media Ecology?

"They think that what they say is communication. Communication is the effect of what you say." -Marshall McLuhan

To understand the force I'm talking about, we're going to have to go back to the mid-century. A time which, like today, was experiencing a rapidly evolving media landscape: Cinema, radio, television, the telegraph, color print, photography, and magazines had all sprung into existence in a generation. While these media feel commonplace to us today, for someone living through that time, it was an incredible shift in the culture.

For some, this time represented an overwhelming but exciting new world. One that was defined not by writing or the printed word, but instead by prolific auditory and visual media. Culture rushed to adopt these new forms of media, but it was also grappling with the influence and power that they had.

In a discussion round table called “Big Media in America” broadcast in 1959 on National Education Television, one student expresses her concern about newspapers, "For example, the advertising, the funny page, the sports, the crossword puzzles. I mean, so many people don't even read the newspaper for the news. They read it only for these things."

Another student adds: "And these new little quickie magazines that you pick up that are a few inches high. And then the radio, you have the five minute news spots. And that what you only get is the most sensational aspects of what's going on in the world."

There were concerns about Cinema: In 1928, the League of Nations Child Welfare Committee released a report saying some delegates expressed fears that “cinema performances happening in the dark with promiscuity of sexes and languorous music should excite the child by appealing to his lowest instincts and least noble passions.” And that “bad habits may result.” This was a problem that could easily be remedied, the committee said, if the technology was developed that would allow cinema to be shown in broad daylight. But there were also more serious concerns about the potential for cinema to be used as a propaganda tool by authoritarian governments.

And Television of course did not escape suspicion. There was much hand wringing about the amount of violence shown in the Westerns and crime dramas that were incredibly popular. But there was also concern about the way television was changing people's habits. A New York Times article from 1949 titled, "What is Television Doing to Us?" reports that, "Whether the art of one person talking to another is to be killed by television is the subject of much energetic debate.” What would this do to society? “Nearly half of the television owners acknowledge that their choice of an evening to go out is influenced by what programs are on," reported Jack Gould. "Political groups and social clubs are feeling the rivalry of television."

In the burgeoning modernism of the 20th century, whether it was cinema or television, media itself was becoming the infrastructure of ritual and community for American culture. Increasingly, people were gathering for and around pieces of media rather than civic or religious institutions.

Hoping to understand the implications of all this, new figures arose. These new cultural commentators and critics sought to study and understand the messages that these media conveyed and the influence they had on society. In Toronto, Canada, one of the people trying to understand this media landscape was a professor named Marshall McLuhan.

McLuhan's work was sprawling, controversial, and shrouded in riddles and poetic language. But his core idea—that the mediums themselves were the messages—would spark a school of thought that would provide a new way of seeing how media influences culture.

"The medium is not something neutral. It does something to people. It takes hold of them, it wraps them up, it massages them, it bumps them around." -McLuhan

This school of thought developed by McLuhan and expanded by his followers would come to be known as media ecology. For the media ecologists, an individual medium represented not just a way of conveying individual ideas that we could then judge or interpret. It was a landscape that surrounded us. One which could literally alter our behavior and even the way we think.

"When you put a new medium into a play in a given population, all their sensory life shifts a bit." -McLuhan

To understand this, think about how your real life physical environment shapes your behavior. If you live in an arid, mountainous landscape, this will cause you to have a very different lifestyle life than you would if you lived in an urban landscape. In these landscape you have some influence over your own behavior, but much of it is ultimately shaped and constrained by the environment itself. You can’t, in the mountains, go down to the corner bodega at 2 am because you ran out of oat milk. Your entire existence has to be structured in a much more intentional way even when it comes to the most basic habits like acquiring food.

And these landscapes don't just affect our habits and lifestyle but also how we perceive the world. Think about how your physical environment might shape the kinds of sensory information you're attuned to as a person. Someone used to living in a city might easily tune out the sound of an ambulance, while someone living in a rural environment where they're more exposed to the elements might notice specific shifts in air temperature and wind direction that signal an approaching storm.

In the same way, the media landscape around you, which is made up of the different individual mediums that you interact with, shapes and influences your behavior. One of McLuhan's key ideas was that each medium extended one of our senses. While this extension of our senses outward makes us more attuned to certain kinds of information in the environment, he theorized that it also numbs us to other kinds of sensory information.

McLuhan and others theorized that the fundamental technology was language itself. In the same way, your understanding of language and the words in your language can shape how you think about ideas, the other kinds of media that you use to communicate and express yourself also shape the way you behave, see the world, and think.

To understand how subtle and nuanced the changes can be that affect our perception of the media we're experiencing, let's talk about the Fordham Experiment. In the Fordham Experiment, they took the same video content and showed it to audiences in two different ways. For some audiences, the videos were projected onto a screen. This means the light is bouncing off a wall and into the audiences eyes. For another audience, the videos were played on a screen. This means illuminated pixels were shining directly into the audience's eyes. Each audience would then write about what they watched. What the experiment discovered was that even when they were viewing the exact same content, there was a dramatic difference in what each audience would write about depending on how they had viewed that piece of content.

So for example, for those that watched the content projected onto the screen, only about 6% mentioned “losing a sense of time.” For the group that watched the content from an illuminated screen (like most of our screens are today) the mentions of losing a sense of time rose to 60%. And this happened with a lot of factors, like whether or not the audience would comment on a specific scene or the cinematic technique. So a relatively subtle change in how the content is presented can lead to a fairly significant change in how the content is perceived: changing what elements of the media we're more likely to notice or focus on.

That's one small shift in form. Think about what happens when there's a larger shift in mediums, where many factors of how a piece of information is conveyed change at once. And when a society suddenly switched to consuming most of their media through a new medium in a short span of time.

V. Amusing Ourselves To Death

"In the 1860s, he would have been unthinkable because he can't talk. But you put him on television and he's dynamite." -Neil Postman

For a media ecologist like Neil Postman, his primary critique of TV was not the individual programs, but instead the landscape that TV presented. In an interview with CSPAN he explains some of his concern with TV News, "The voiceover says more shooting in Beirut today. We see some film of a street perhaps in Beirut, a body on the floor. We hear shots. This image is powerful. So people know of Beirut. They know there's shooting in Beirut. Do they know who's shooting at whom or why or what is the historical context for this?"

Another of his main concerns was the way television was structured around advertising, "The function of television in America is to gather an audience, which can be sold to advertisers.” Which he theorized significantly diminished its ability to present the serious discussion of anything. "American television knows that the best way to gather an audience is to provide something that is amusing."

TV, according to Postman and McLuhan, converted everything, even disasters and wars, into entertainment. One of the strongest realizations I’ve ever had about the reality of this came have come from watching television coverage of United States Elections. Postman explicitly critiques the TV format of political debates, but the way TV warps our perception of politics extends well beyond that. If you watch an election night coverage on any major channel, and pay close attention to the tone, language, visual, and editing they use to convey the information, the format of presentation is extremely similar to the coverage of sports. The whole event is made to look and feel as much like a boxing match as possible where the two sides are duking it out as we look at an instant replay, blow-by-blow account of what just happened in a swing state when the polls just closed.

I don’t find it hard to argue that this intense, entertainmentification, and dramatization of an incredibly important, nuanced, and complex event for our nation, is not particularly helpful in generating an informed public.

When it comes to the role of advertising, film editing theory, like the Kuleshov Effect—which shows that our perception of the meaning of a shot can change depending on what the filmmaker cuts to next—can help us understand Postman’s critique. How is our perception of the meaning of a serious topic affected when it's juxtaposed against and interrupted by an advertisement for dish soap?

Through a traditional lens, we might examine television media by looking at the violence in a specific Western, or a news report that spread misinformation. But through a media ecology lens, we can see that the bigger impact that television had on our culture probably had more to do with the way information was presented by the medium.

When we adopt a new media landscape, it also changes our social and physical habits. With the arrival of TV, the social gatherings in public that the Cinema provided gave way to more time spent in intimate family gatherings around the TV in the home. Some parents were concerned about their children spending less time outside because of TV, while others saw this as a good thing since it was keeping them off the streets.

But perhaps the most important idea from the media ecology perspective for what I want to illustrate for you here in regards to Cinema, is that a medium and what it represents and means to a culture cannot be understood in isolation. Because what a medium means to us, the message it conveys, comes not just from its inherent properties, but from how it relates to the other mediums around it. And when we begin to understand this, we'll see clearly how no matter where the film industry goes from here, cinema has already undergone a significant transformation into something new.

VI. The Message of Cinema

To understand how the meaning of cinema has evolved, we must first look at what it represented in the past. If we return to time when The Exorcist was released, even though cinema had already fallen from its peak in the 30s, it was still one of the most significant cultural forces.

This was a world where, if you wanted to know what was happening or be entertained, you could turn on the TV, or turn on the radio, if you're fortunate enough to have one. But using these devices, you would only be able to see or hear whatever happens to be broadcast on the few available channels at that moment. If you're not interested in what's being shown or said at that time, you have no control beyond simply turning it off or changing the channel. And these technologies were still largely built around communal spaces. Families would gather in the living room to watch TV, or the radio might be on in the kitchen. Your media consumption was often linked to the consumption of those around you.

To access more information, you'd need to physically retrieve a newspaper or a magazine. The information there would be dense and low fidelity. Illustrations and photographs, written reports of things happening in the world delayed by a day or sometimes weeks or months. For musical entertainment, you could buy or listen to records, turn on the radio, or go to a live performance—again engaging with media experiences that were both curated by others and communal.

And then, in the midst of all this, you decide to go see a movie. The movies in this environment share a lot of features with the other media at that time. You still have limited control over what you consume, and you can only go see a movie at the specific showtime. But the movies also stood apart as an entirely unique media experience.

In this landscape, the movie was arguably the pinnacle of sensory entertainment. It was the biggest cultural spectacle media could provide. Its images were the biggest and the most vibrant available. Unlike books, newspapers, or magazines, and even the low fidelity of early TV where you had to focus your attention and participate in consuming the media, when watching a movie, you could sit back in the dark and essentially allow the film to wash over you. The movies guided you through the story with an almost hypnotic, trance-like quality. You were absorbed. They might sweep you away to another world, transport you to another time, and all of this alongside a crowd of people. It's not hard to see how the movies were one of the most captivating and alluring media experiences at that time.

When cinema arrived, it didn't just bring new kinds of art and stories. It introduced culture to a new kind of experience.

It was partly a commodification of the theatrical experience, but it was also a ritualistic, social, and almost religious consumption of media. Unlike a play, audiences from all around the country or even the world could be united around having seen the exact same piece of media. But it also introduced a new type of sensory experience. These were large, exciting images that commanded the audience's attention. A movie star could be lit, captured, and projected in a larger-than-life way that would have been impossible in any prior form.

Taking into account the media ecology view, we must ask how did these movies change our perception of ourselves as humans? Unlike the print-dominant forms, cinema was a medium where images, language, and music worked together to create feelings. You could analyze movies, but unlike text, they didn't really require analytical thinking to be understood. All of this together meant that they were a uniquely powerful cultural force. This distinct and uniquely evocative experience that cinema represented within the culture explains why movies like Jaws or The Exorcist could have so much impact and influence. But what changed? Well…

VII. welcome to the hypermodern

"But when I was a boy, we didn't have a telegraph, didn't have a telephone, of course, no electric lights, no any of these other things which have come out to bother us." -An 87 year old farmer in 1929.

"I remember when we didn't have television and I was forced to be creative all the time and to make up all of my own games and to play at acting all myself and nothing was ever presented to me so that I could simply sit and absorb it." -Student in 1959

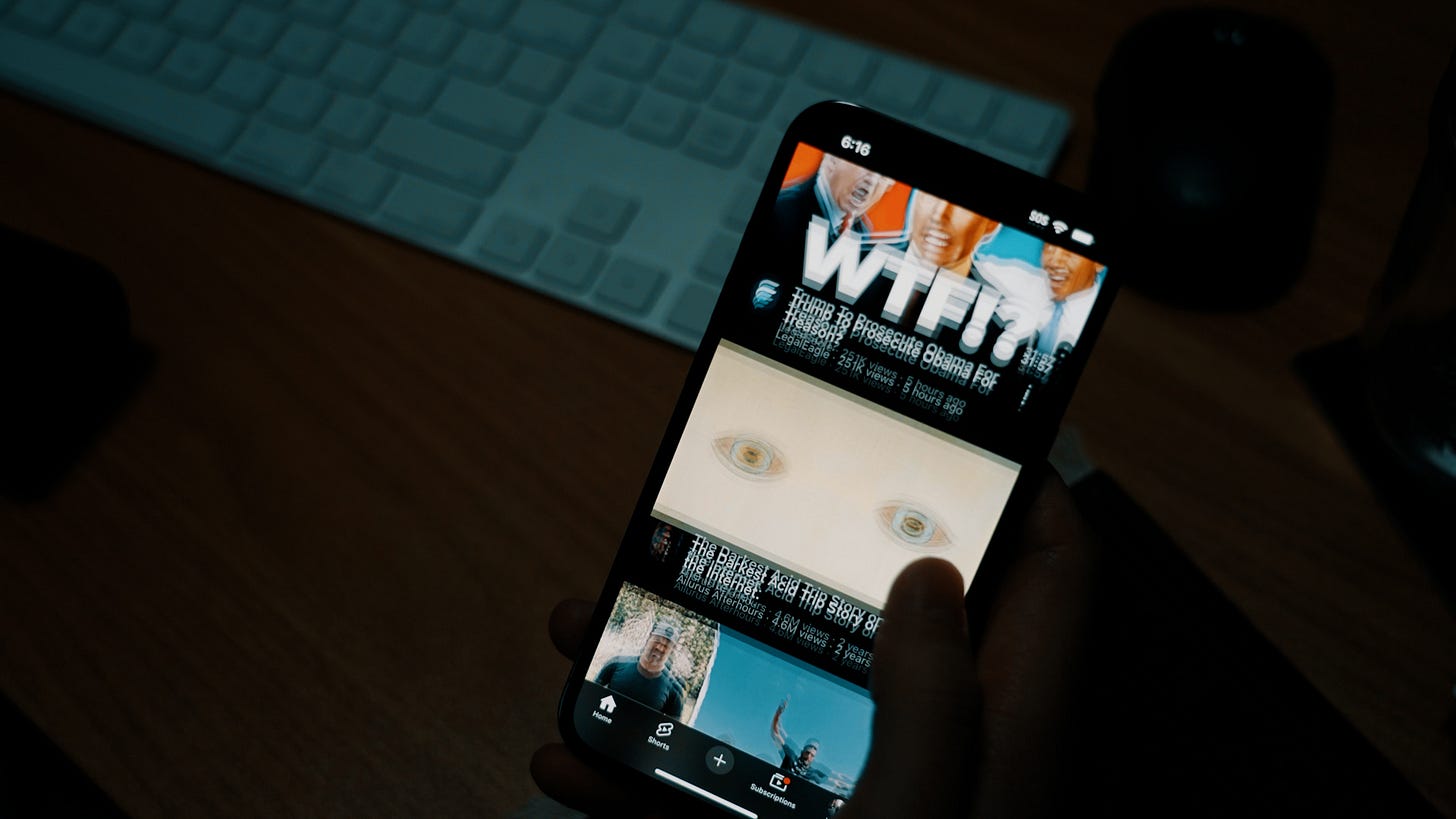

You wake up and immediately open your phone. Whether you choose Instagram, TikTok, Twitter, or Facebook, you're hit with a torrent of shifting information, algorithmically tuned to be the most interesting, attention-grabbing content possible. One flashy image or video after another. You can see videos of the most exciting or horrifying events happening around the world delivered straight into the palm of your hand before you even get out of bed. If you set down your phone and turn to your computer or TV, you have access to almost every kind of recorded media from any time period or part of the globe available for you to choose from at any time. You can watch an independently produced YouTube channel. You can watch the news in HD showing you violent or catastrophic events. You can watch children's programs. You can watch videos constructed entirely by artificial intelligence. Almost anything you can imagine lies at your fingertips completely at your control to pause, rewind, play again, or share.

A lot of attention is given to how social media is shortening our attention spans, but I think the story is much more complicated. A full analysis of smartphones, internet streaming, and social media from a media ecology perspective could be its own book, so I'm just going to hit some of the highlights here:

From a media ecology perspective, people have become acclimated to an environment of rapidly shifting context. We expect an increasing variety of content to be constantly accessible and easily switchable. Increasingly, very little media consumption is communal or tied to a specific time anymore. You might watch a movie or some TV with friends or family, but what you watch is now usually disconnected from what most other people around you are watching. Even if you and a friend are watching the same show, the chances that you both watched the same episode the night before is low. By allowing us to watch whatever we want at any time, streaming has reshaped collective viewing. For internet content, personalization algorithms only push this further.

While the mediums that McLuhan and Postman were examining were relatively simple, with the introduction of the computer, we enter an era of what I would describe as hyper-mediums. These are mediums that themselves contain layers of smaller mediums. So if you're reading this essay right now on your phone, the content that I'm sending you is filtered through the medium of written text. There are certain biases and effects that are inherent to text itself, but then that's also being filtered through the medium of Substack, your email app, or the browser, how the text is presented to you, the comments and other meta design elements that surround the text. Your perception of what you’re reading will likely be impacted by how positive or negative the comments are or how many likes the post has. And then beyond that, this text is additionally being mediated by the form factor of the smartphone itself. The fact that you can carry it around with you. You might be reading this in bed or on the toilet or on the subway. Each of these contexts would in some way inform the experience.

For McLuhan, the mediums of the past become the content of the current mediums. And we're seeing that happen right now: So if the video of cinema and television and the words and photos of print are the content of our social media feeds, what is the new medium we're consuming and what is the message of that medium? Well, the medium is the feed itself, the algorithm itself, and our consumption of that. Tech writer Alberto Romero posited that when we're scrolling through short form video, it's not the content itself that delivers a dopamine hit, but the moment we scroll, the millisecond where we're anticipating what might come next—whether it's something scary, funny, interesting, or boring. It's the hit of anticipation that we're consuming.

Here, Neil Postman's concerns about the influence of advertising on a medium, rather than disappearing in the transition from TV to social media, only become more amplified. Like television, the goal of the feed and the algorithm is to gather an audience and sustain that audience's attention so that it can show it more advertising. The result of this is that it will show you not what's best for you or the most important information, but whatever is the most attention-grabbing.

For mediums of the past, like cinema, a book, or record, by the time you consumed the content, you had already paid for it. Those making the media were incentivized to make the experience a good one so that it spread word of mouth and more people bought it and so that you might be more likely to buy something from them in the future. But there was little specific incentive to hold your attention for as long as possible.3 That all changed with television with the move to an advertising model in which more time spent watching by the viewer translated directly into more money for those creating the content and distributing it.

In an online world defined by incentives to grab and hold your attention subtlety, nuance, and quietude do exist, but they're fairly niche products delivered to a minority of viewers. The vast majority of what filters to the top of these algorithmically curated platforms is the loud stuff that will grab and hold your attention. And this affects everything from Netflix and Instagram to the what you're reading right now4.

A significant aspect of the smartphone is the way it fuses the medium of the remote control with the media itself. The medium of the smartphone is a platform that we use to bring stuff to us (both in the digital world and in the physical world: doordash, “Find My”, Uber, dating apps) or to control what we're seeing or the world around us (Google Maps, camera apps). There's nothing on our smartphone that we're truly subjected to and don't really have control over. Even the sensation of grasping it in your hand is the ultimate sense of control over the media you're consuming. I'm not saying being able to control our media is bad, and this might seem like a minor difference, but I think it has a significant psychological impact on how we perceive the media as we consume it.

The act of craning our necks downward for hours every day literally reshapes our bodies and our experience of the world. We doomscroll, we talk about misinformation, internet bubbles, and write think pieces about the attention economy, some people are quitting their phones entirely or doing dopamine detoxes, but this is already the water we swim in. If McLuhan and the media ecologists are right, the shift to spending hours a day consuming media through a new medium, our phone, changes not just how we perceive the media on our phone, but the entire world around us.

We have stepped into a new media environment, and now we must understand and respond to how it's reshaped our habits, society, and perception. The big takeaway is that in contrast to a lot of the media of the past, the current media landscape emphasizes control, portability, individualization, total participation in a global landscape of media, and perception mediated by desires through an algorithm.

Now within this new landscape: think about the experience that going to the movies represents. In the 1970s when you went to a movie, you were stepping out of a world of relatively low fidelity visual media into an intense multi-hour visual spectacle. In 2025, when you go see a movie, you're probably taking a break from the most overwhelming sensory spectacle humanity has ever created.

When you go to the movies, now you're committing to a single piece of media for multiple hours, which you must watch at a predetermined time with a group of people. A piece of media you have no control over. The images on the screen move at a much slower pace than what you're used to seeing on your phone, and if you aren't interested in it, you can't immediately change it to something else. Even big, exciting action films can feel deliberate and calculated in a world where you can watch actual countries shoot missiles at each other, the most insane stunts you’ve ever seen, or real-world car accidents back to back in the instagram reels feed.

So cinema, the medium that used to feel like the height of spectacle, which could send culture into a panic, now often feels like a relatively slow, linear, and focused journey through a single narrative. In this landscape, it's the phones and the content on the phones that are inciting the kind of moral panic and cultural change that The Exorcist did.

The printing press, electricity, the telegraph, and television weren't just tools of communication, they allowed society to adopt new shapes, new ways of living and interacting with one another. The rapid adoption of smartphones, social media, algorithmically tuned recommendation feeds, and now AI is currently reshaping the landscape of our society, the same way it was reshaped in the early 20th century by the mediums that arrived then. And cinema's place within this new landscape is different than it was 50 years ago, just like it was different in the 70s than it was in the 1940s. Now, collectively on average, compared to all the other media we consume, it represents something else, a different kind of experience.

VIII. “Bad Habits May Result”

My goal with all of this is not to construct a narrative that phones are bad and movies are good. For McLuhan, the media ecology approach wasn't about trying to make moral assessments about which mediums were better than others.

"I seek to perceive, not to conceive what's in front of me. And perception is exploration." -McLuhan

Instead, he was more interested in contemplating the media environment we're actually living in. I do think there are some notable downsides to the hyper-modern media landscape we all live in now,5 and I think we should do everything we can to document, understand, and then overcome whatever negative effects these new mediums might have. But especially for those old enough to have one foot in the media environment of the past, it can be easy to fall into a kind of understandable nostalgia where we hold up the mediums of the past as somehow more morally pure than the mediums that are most popular today.

This has happened with things like the novel, which was initially treated as populist distraction, while today there's almost a moral panic about the fact that fewer people read literature. And we're seeing this happen with movies: When the big blockbusters of the 70s like The Exorcist and Jaws came out, a lot of filmmakers and critics wrote them off as populist escapism, but now they're treated as something closer to a form of art. So it would be easy to romanticize film somehow as a more pure or unblemished form of media, but that's not what I'm trying to do here.

The Movies have downsides. Producing one has been much less accessible to the average person than other forms of media, and so channels of distribution have traditionally been controlled by corporate interests. Right now, for example, No Other Land, an Oscar-winning documentary about Palestine, is not available for viewing in the United States six months after winning, because nobody's been willing to distribute it here. A repeat of what happened in 1974 with the documentary Hearts and Minds a film critical of the Vietnam war.

And while cinema's power as a transporting, emotional, and almost hypnotizing storytelling medium is what makes it so enticing, it's also what makes it a powerful tool for intentionally and sometimes unintentionally perpetrating harmful ideas, stereotypes, and ideologies through propaganda. Cinematic propaganda wasn't just an issue in Nazi Germany, it continues to be produced in subtle and sometimes insidious ways that audiences often don't even realize.

Another limiting factor for cinema is how it has been transformed from an affordable cultural commodity into what is almost a luxury experience. Back in the 40s, when over 60% of Americans were attending the cinema, a movie ticket was only 25 cents, which would be about $4 today. These days, for many Americans, a trip to the movies can be cost prohibitive, pushing it further towards being an activity reserved for special occasions and the middle and upper classes.

So as much as I have deep concerns about the new hyper-modern technologies like phones, social media, shortform video, etc., this is not about vilifying or blaming those things in order to say cinema is somehow inherently perfect or a great medium by contrast.

But neither is my goal to proclaim that “cinema is dead, this time it's real, and now I've found the true culprit!” When Wim Wenders made Room 666 in the 80s, a documentary asking the question "Is cinema about to be a dead language?" many of the filmmakers he interviewed seemed to think it would be. I think the opposite is true.

The language of cinema is far from dead. Instead, it's been absorbed by the mainstream culture as the primary language of communication. A lot of the media we now consume on our TVs and phones uses cinematic language. These mediums are essentially a form of post-cinema that adopt the visual grammar of filmmaking. In this world dominated by visual cinematic grammar instead of literary grammar, valuing and studying the cinematic roots of all this is only becoming more important.

So I'm saying the movies have changed, and on average probably won't quite feel the same. But that doesn't mean I think they've ceased to be relevant, that they won't continue in some way to provide interesting, meaningful, culturally relevant experiences and play a role in the media landscape for a long time to come. But if we want that to happen, if we want moviegoing to continue to be an accessible medium for people, we need to give up false hope that cinema will magically return to what it was in a previous time and stop trying to force it to compete with the new media landscape by being something that it isn't. Instead, the way forward for cinema is to understand exactly what it has to offer to us that social media, phones, and television cannot.

IX. An Unofficial Guide to Saving Cinema

So let's talk about how cinema can survive. It's very possible in the future we'll go down a path where a movie is just a different type of content that plays on our TV or phone like everything else. In this future, theater screenings will be treated as rare events or simply a marketing ploy. We're already headed in this direction to some extent. But I don't want this to happen, and I think it can be avoided. So let's look at how:

First, like it did in the 20th century, cinema can once again become bigger. This is already happening, the increasing prevalence and promotion of IMAX represents this century's version of CinemaScope or VistaVision—and it works to some extent. Better sound along with bigger, more immersive visuals can still provide some of the grandest sensory experiences available in media today. Some filmmakers like Michael Bay even seem to be competing with the intensity and rapid-fire pacing provided by internet video.

But while I love the trend towards impressive large-format filmmaking with great sound design—and seeing some of the scenes from this year’s Sinners on a big screen is one of the most stunning media experiences I've had this year—I think trying to consistently out-compete internet media in terms of creating the largest sensory spectacle is ultimately a losing battle. Your phone might be tiny in comparison, but it provides pure uncut dopaminergic entertainment and novel images in a way that even the biggest cinematic images these days will struggle to keep up with. I'm not saying internet video is better, or that these bigger, more cinematic movies aren’t good. I just don't think cinema will win only on the basis of trying to be the entertainment spectacle of culture when we're carrying around one of the most intense media spectacles ever created in our pockets every day.

Instead, where cinema can win is where it continues to provide something that your phone cannot. And this lies in its ability to use that sensory experience to immerse you in an emotional narrative. The biggest advantage that cinema has going for it is time and focus. Cinema is one of the only forms of storytelling remaining that asks you to sit and give your full attention to a complete story for an unbroken two to three hour chunk of time. Sure, you might binge watch a TV show or doom scroll for three hours, but those aren't contained narrative experiences consumed in a single sitting. Short form video shifts your attention every few seconds and TV breaks for episodes and ads and happens exclusively at home in a distraction-laden environment. You can listen to a podcast or audiobook for three hours, but again, that three hours won't be an entire narrative, and you likely won't be giving it your undivided attention.

With a movie, you're locked into a single, overwhelming experience for hours, with no breaks or division points. And while obviously people are going to whip out their phones, even at the theater, the key is that the intention of the form is for you to be mentally immersed in a complete story without distractions. And even if not everyone consumes it this way, this changes what it is.

A lot of TV is specifically made to be on in the background. Netflix intentionally produces what it calls second screen content with the expectation that audiences are going to watch it while they're on their phones. So this means that even if you sat down and completely immersed yourself in one of these Netflix shows that is made to be on in the background, you aren't going to get the same experience as if you immersed yourself in something that was made to be immersed in. Even if you aren't on your phone while you're watching a show made to be on in the background, you're still watching something that has been made for the level of attention of someone who is.

Cinema, meanwhile, is made for the theatrical experience6 where an audience is going to give it their undivided attention. When people hear filmmakers say "this is made for the big screen," or advocating for the theatrical experience I think it's sometimes perceived as elitist or nostalgic posturing, but having the theatrical experience as the end goal for filmmakers as they create the movie really shapes the kinds of movies that filmmakers will make and how they make them. When a movie is made for an environment where you're supposed to give it your full attention, the effects of that will impact the viewing experience even if you end up watching that movie at home.

Cinema's unique demands on our attention and time in this media landscape means that movies are asking a lot more of an audience in terms of time and attention commitment relative to other media today, but this is exactly what makes them a particularly powerful form of media in the landscape. Given this commitment, filmmakers have a unique opportunity to sweep up and transport audiences in an emotional, evocative experience that other kinds of media might not be able to. Movies that really want to succeed today need to understand the bargain they're striking with audiences, and at least attempt to deliver something worthwhile in return for what they're asking.

But within this space, movies also now have an opportunity to be something much more inherently meditative and contemplative. I don't mean that all movies need to be slow, art-house fare, (although I think that's great and more people should give it a shot) I mean even a basic drama can create space to think about a single subject, character, idea, world, or feeling for hours in a way that audiences probably aren't doing with other media they're consuming. I think the movies that will stay relevant will be the ones that use this time in a way that rewards the audience for doing so, instead of just providing cheap entertainment escapes. It's not that cheap entertainment escapes are bad, or that movies should never try to do that, but those are now freely available in your pocket whenever you want, and paying $20 to go sit in a room for a cheap entertainment escape won't feel as worthwhile when you can get one for free at home.

We also need to recognize and lean into the communal value of movie theaters and the movies themselves. These days I often hear people complain about the theatrical experience. People are on their phones or there's distractions, but there can really be a magic to watching a film with a group of people, and the movies need to try to retain that. Even when everyone is quiet, you can feel something, the experience changes when you're with people. And in the same way movies being made for theaters impacts the demands they place on our attention, movies being made for theaters also means they're made to be watched with a group of people.

I love watching movies alone, but most of my best movie memories involve a theatrical or group experience. Even at home, “the movie night” creates a unique social opportunity for a group to experience a complete narrative together in a way that pretty much no other media currently provides. Sure, you can watch TV together, but it's hard to do that with a group of people who are all living different lives. You have to coordinate together to watch the same show and all be on the same episode at the same time. Consuming a movie with a group provides a unique opportunity to all experience a single narrative together and then discuss it afterwards. In our increasingly socially fragmented and individualistic society, where our media consumption is more and more specialized and presented on tiny screens just for us to see, there's a value in getting to experience something more communal.

And movie theaters, with their progression towards premium experiences and larger multiplexes, have kind of been leaning away from the value of the communal experience rather than into it. Theaters are often trying to compete with streaming by trying to make the theater as comfortable as your living room. But while I love a heated lounger as much as anyone, I think this might not be the most productive approach in the long run. Many of the best theatrical experiences I've had come from smaller, less comfortable indie theaters in my town where even obscure movies would sell out and there was a sense of community surrounding each screening. Theaters can lean into this more by making memberships more affordable and accessible and by providing lounge and gathering areas outside the screens instead of literally designing the spaces to minimize human contact and interaction, shuttling you like cattle in and out of the screen.

I'm not insinuating these are the only things that make the movies valuable these days, or that this is an easy or surefire way to save cinema, but I think if the movies want to continue to carve out a valuable, vibrant, successful place in the media landscape of today, they need to capitalize on what makes them unique instead of trying to morph into what everything else is in order to compete with that. Or by doing what they’ve mostly been doing—sticking its head in the sand and pretending the problem will go away while theatrical attendance continues to shrink.

This narrative I've been crafting focuses mainly on Hollywood, American movie-going, and the blockbusters that draw the largest crowd. And while similar dynamics are playing out around the world, each country has its own unique set of cultural, economic, and political dynamics that affect how well the theatrical experience thrives. And the world of indie and international film, along with many independent boutique theaters, are already leaning into much of what I'm describing here and how they make movies and present them. If the Hollywood studios want to stay relevant, they will have to catch on, otherwise they're fated to continue down the path they're already on: towards simply becoming content production engines for their own streaming platforms, which will compete with all the other content on the internet.

The movies should be interesting, thoughtful, and worth your time. They should continue to be immersive, visual, sonic, sensory experiences. They should continue to be communal experiences, an event that we go to or consume with a group at home, rather than just another piece of content to be consumed the same way we consume anything else. Not because of some kind of elitism where cinema is superior, but because it offers us a unique media and cultural experience that other forms of media do not.

Cinema will never again have the kind of cultural dominance it had in the 40s, and it's unlikely it will even return to the influence it had in the 70s. To imagine it would would be wishful nostalgia, but as the industry faces the biggest shakeup it's seen in 80 years, I believe it can continue to be a valuable and relevant cultural experience for a long time to come, as long as we value it for what is actually unique about its ability to transport us together.

In 1930 (the earliest year from which accurate and credible data exists), weekly cinema attendance was 80 million people, approximately 65% of the resident U.S. population (Koszarski 25, Finler 288, U.S. Statistical Abstract). The Decline in Average Weekly Cinema Attendance, 1930-2000 Michelle C. Pautz

“A Century in Exhibition – The 1950s: Turmoil, TV, and Technological Innovation” Box Office Pro, April 15 2020

Theoretically there would be with Newspapers and Magazines—the more you read, the more ads you see, but they had no metrics for actually measuring if you saw the ads or not, and these incentives were balanced by subscriptions so the “hold your attention” incentive would have been much softer than online platforms where they can measure down to the second how long you watched, how much of the ad you watched, etc.

I of course, try not to succumb overly to pressures towards clickbait or “retention hacking” as YouTubers call it, but these incentives are so strong that they’re nearly impossible to avoid if your income is at all tied to these platforms. One of the reasons I like Patreon/Substack is that a subscriber model (has some of it’s own problems) but shifts/balances the incentives considerably and makes room for better/different kinds of content. So consider supporting the creators whose work is meaningful to you.

Jonathan Haidt, Jaron Lanier, and The Center for Humane Tech, among others have done and excellent job documenting some of these.

contra Scorsese (while I think he has a valid point about Superhero films) I think these days I would argue that something being made for a theater is actually what makes it cinema by definition.

Wim Wenders said he was most impressed by Antonioni’s response to the Room 666 prompt, which is why he left it unedited – including the ending where Antonioni turns the camera off, producing one of his characteristic moments of ‘dead time’, lingering on the empty, inanimate space after the character has left the frame.

Your essay made me think of this part of Antonioni’s statement in Room 666:

‘Of course, I’m just as worried as anyone else about the future of cinema as we know it. We’re attached to it because it gave us so many ways of saying what we felt and thought we had to say. But as the spectrum of new technologies gets wider, that feeling will eventually disappear. There probably always was that discrepancy between the present and the unimaginable future. High-definition video cassettes will soon bring cinema into our houses; cinemas probably won’t be needed anymore. All our contemporary structures will disappear. It won’t be quick or straightforward, but it will happen, and we can’t do anything to prevent it. All we can do is try to adjust to it. In Red Desert, I was looking at the question of adapting – adapting to new technologies, to the polluted air we’ll probably have to breathe. Even our physical bodies will probably evolve – who can say in what ways. The future will probably present itself with a ruthlessness we can’t yet imagine.’

I’d be very interested to hear Antonioni’s thoughts on recent developments in AI. Red Desert not only observes the effects of mid-20th-century industrialisation, but is also visibly infused with those effects. The camera acts like a robot, getting distracted by the oil-carrying black tube on an offshore platform. The editing mashes images together with a machine-like indifference to the audience’s need to comprehend how one scene flows into another. And the score seems to have been composed and performed by a choir of robots who know only the music of the factories, and who see no reason to learn any other kind.

In your post about AI, you say that:

‘AI generated videos are all “post-cinema” completely divorced from any of the original technique of cinema. The technique of “filmmaking” has entirely evaporated, that which “looks cinematic” is all that’s left.’

In Red Desert, I think Antonioni tries to create the sense that the film has been shaped not only by human agency and technique, but also by the robotic equivalents of agency and technique. Elena Past refers to ‘petrocinema’ in her reading of some scenes; the film’s dependence on and immersion in industrial processes transforms it on a fundamental level. Perhaps Red Desert is more attached to the inanimate world than it is to the human race. It’s a fascinating example of how ‘the medium is the message’, when the medium consists of world-eating factory products.

David Ehrlich recently wrote that ‘AI tools are useless without a bedrock of human creativity to steal from, and its certain failure will be an expensive testament to the fact that algorithms will never create new things. Even a five-year-old can sense the difference between something that was made with care and something that was generated without thought. People are born knowing the difference, and so there’s no sense in accepting that we have to let “progress” condition us otherwise.’

Antonioni might point out the generation who are ‘born knowing the difference’ will one day die out, and that our understanding of ‘creativity’ (and how much it belongs to humans or could potentially belong to algorithms) is likely to evolve over time. If that makes it sound like he would be unsympathetic to current fears about AI, or mindlessly accepting of these changes and the impacts they would have on people, I would again point to his admission that he was frightened by the changes besetting cinema in 1982, and his acknowledgement of the unimaginable ‘ruthlessness’ (I think it’s more like ‘ferocity’ in the original Italian) with which the future will alter our way of life. [1/3]

wow i think reading this instead of watching the youtube video incites the same type of immersive contextual effect you talk about. it plays with my attention in a more thoughtful and meaningful way.

i also feel like your meta lens on cinema is so cool especially when the themes of this post relate to what it means to be human at heart (building community, sharing stories)