Why AI "Art" Feels So Wrong

Reclaiming Art in the Age of AI

This essay was originally published in video form on YouTube and Nebula.

When I encounter the increasing number of AI generated images, videos that are flooding the internet, I don’t know about you, but I get a very strange feeling. I have a kind of gut reaction that something is wrong with these images.

There is part of me that is skeptical of this gut reaction—am I falling into a trap that so many generations have fallen into before? Am I, as proponents of AI might suggest, just reflexively rejecting the next logical step in technological advancement because it represent an uncomfortable change? Am I merely repeating the pattern started by Plato when he critiqued the development of writing, arguing that it would cause humans to cease remembering?

Or does this gut feeling that something is “wrong” about “art” generated by AI, speak to something deeper and true? Does it reveal something about what art is for us as humans? And that whatever Art is, trying to generate it using AI violates that thing in some way?

AI in Hollywood

Tilly Norwood is an AI “actress” created by Particle6—a UK based company that bills themselves as “Europe’s leading up-and-coming AI production Studio”

Tilly caused an immediate, strong backlash from many in Hollywood, actors frustrated at the idea of being replaced in an already competitive industry, with some seeing the Artifice of Tilly as unsettling in a deeper way. Emily Blunt, reacted to Tilly by saying “Please stop. Please stop taking away our human connection.”

Even if the technology is not yet developed enough for Tilly to show up in the next season of House of Dragon, it’s clear that some in Hollywood are not opposed to the creeping advance of AI, some talent agencies have reportedly been circling Tilly, Ridley Scott has said he’s “trying to embrace AI” and Blumhouse’s Jason Blum argued in a reaction to Tilly Norwood, that AI is here to stay whether we like it or not. That Hollywood shouldn’t stick it’s head in the sand but should instead embrace AI, “as long as it can be done ethically and legally” he made sure to clarify. Ashton Kutcher called AI “an amazing tool that we should learn to work with.”

This is the most common refrain in support of AI—that it is just another tool. That rejecting AI would be like rejecting digital cameras, or computer animation. And it’s this argument that the creators of Tilly use in their response to the backlash:

“I see AI not as a replacement for people–but as a tool.” “She is not a replacement for a human being, but a creative work - a piece of art.”

But is Tilly art? Could Tilly be used to create art? Is AI just a new paintbrush we can use to put the strokes the canvas? Or is it something else?

Cave of Forgotten Dreams

In Cave of Forgotten Dreams director Werner Herzog takes us into the Chauvet Cave in France, to see the oldest paintings ever discovered.

J. F. Martel writing about the film in his book Reclaiming Art in the Age of Artifice says: “In the images this prehistoric people have bequeathed to us, we get a glimpse of something like a shared humanity, but we also gaze into a stranger part of ourselves, something reaching to the depths.”

Seeing works of art made some 30,000 years ago, there is a striking sense of familiarity. There is something in the very activity of creating art that feels instantly recognizable as human. An impulse which remains with in us despite such a vast passing of time and how much society has changed across that span.

But we also encounter in this cave, something else—what Martel calls a stranger part of ourselves.

What we find looking at this art is the mystery of who the the people painting these images were, and why they painted them? It’s as if we discovered signs of alien life, only to realize the aliens are us, that our own existence is just as mysterious and startling as anything else in the cosmos.

Even if we cannot know what these cave paintings mean, there is a profound and moving mystery in the question of their meaning itself.

These images don’t just represent the existence of something or someone, but a self-awareness of that existence. The existence of the art is existence itself expressing itself for others to see.

What we don’t often think about, is that despite how much art has changed, despite all the technological advancement and scientific knowledge we’ve acquired since these cave painters did their work, we are still caught in this mystery today.

Art is still mysterious, and true works of art still expresses the mystery of life itself.

According to Martel art, “demands that we feel and think the mystery of our passage through this body, on this earth, in this universe…” and “...bears witness to the bafflement that the mere fact of existence elicits in our brains.”

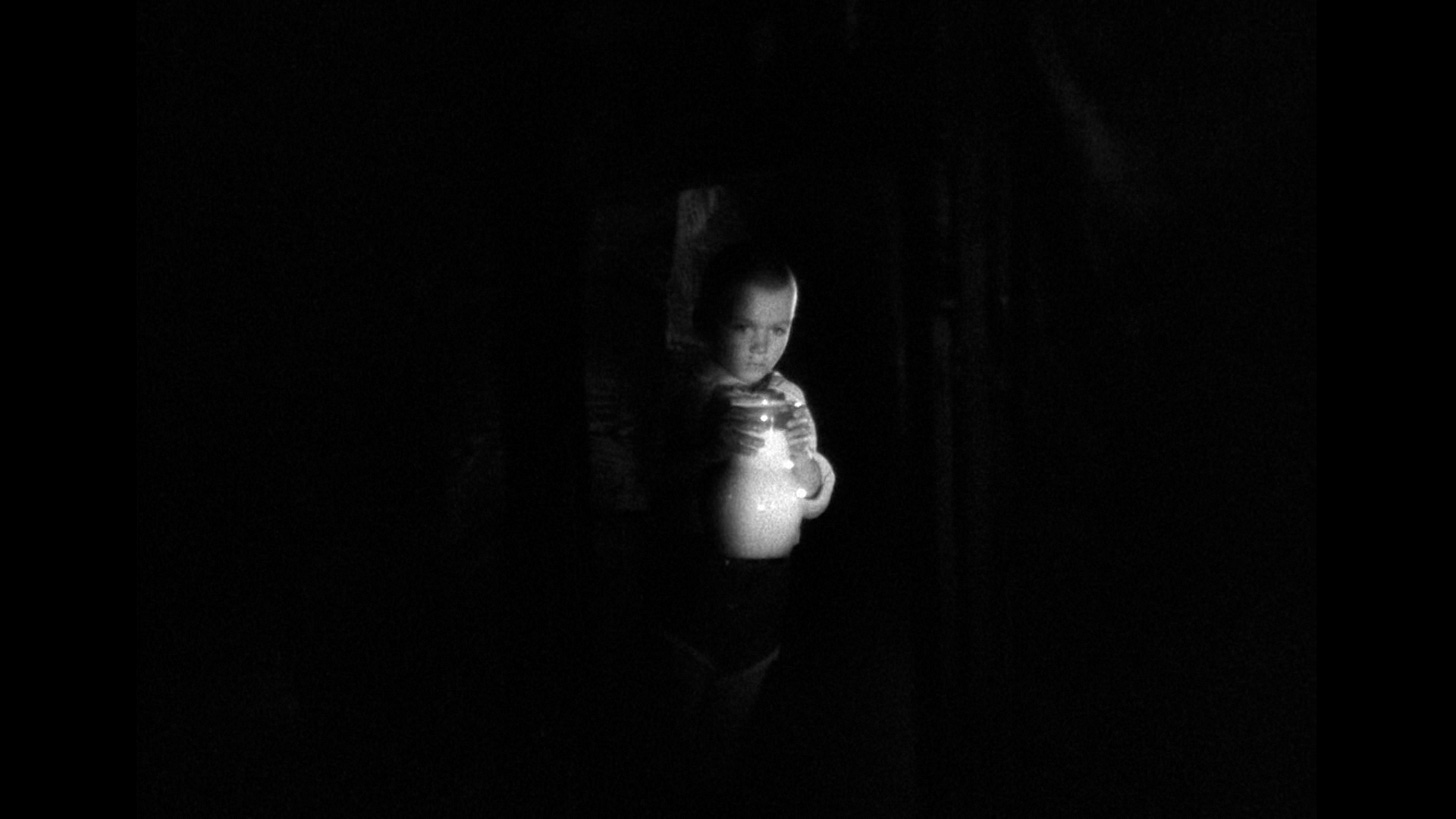

What is the impulse that connects the intricate carvings in Angkor Wat, the Chauvet cave paintings, and the Sistine Chapel, with the mournful beauty of Debussy’s Arabesque No.1, or the hauntingly poetic images crafted by Andrei Tarkovsky in The Mirror?

I see in all of them an attempt to express something the artist experienced, but struggled to quantify. An attempt to express a mysterious part of life that cannot be put into words. A desire to leave not just a mark on the world, but our mark, a mark that says something about who we are and our experience of life.

Art is what allows us to communicate about these mysteries. To share between two humans the unquantifiable aspects of our existence.

Cave of Forgotten Slop

OpenAI, the company behind ChatGPT recently released Sora2, an AI model that allows you to easily generate AI videos that sometimes look startlingly real along with a platform that allows you to view an infinite stream of these artificially generated videos.

Scrolling through Sora induces a kind of dizzying uncanny feeling. There is of course something familiar about this: it looks, at moments, like I might be watching a TikTok, or instagram reel. But there is also something alien and strange about it. At times it evokes a chuckle, more at the nihilistic absurdity of the thing itself than any given video or joke created by the platform. Yet the overwhelming feeling I get, looking at Sora, other platforms that feature streams of AI generated images, Tilly Norwood, or reading a poem generated by an LLM, is a strange sense of emptiness.

There is, to me, a perceptible vacancy to the entire thing, while the occasional AI image might initially grab my eye, I am not drawn in by the curiosity I feel when a human work of art grabs my eye. I do not want more, I am left simply asking why does this exist? What is it for?

Art/Artifice

You can ask an image model like Midjourney to generate a cave painting in the style of the Chauvet cave and you’ll get something like this:

Setting aside the fact that this obviously wasn’t skillfully crafted onto the contours of rock 30,000 years ago, it would be easy to critique this image by pointing out which details it gets wrong, tallying up all the ways in which the images do not measure up to the original in terms of quality and style. But I think doing so would miss the point, because this image, even is it got the details right, would still be missing something that the original paintings have.

But what exactly is missing? And if this generated image isn’t art than what is it? What do we call it?

To answer these questions I’m going to draw on the distinction made by J. F. Martel between "Art, and what he calls “artifice.”

In our lives–even long before the advent of AI–we have been surrounded by and inundated with designs, photographs, paintings, illustrations, graphics, symbols, videos, animations, and other creative works.

Within this huge landscape we find the stuff we typically call art, but we also find the same skills and techniques that are used to create art, used to create a lot of stuff that is… something else.

Most of us would probably agree that Van Gogh’s Starry Night is a work of art, but probably would not think of a Stop Sign, or an event flyer as art in the same sense.

Martel calls this other category: artifice.

It’s important to note that Artifice itself is not bad. There is obviously artistic craft and skill involved in the design and creation of artifice. Intent, creativity, composition and color theory are employed to create an effective road sign or event flyer.

So this distinction is not about diminishing the talent that is often needed to create good artifice or the necessity of artifice in our society.

Instead the distinction between Art and Artifice lies in the purpose they serve both for the artist as a means of expression, and to the viewer as a means of relating to that expression.

Martel says: “Artifice foregoes the revelatory power that is art’s prerogative in order to impart information, be it a message, an opinion, a judgment, a physiological stimulus, or a command.”

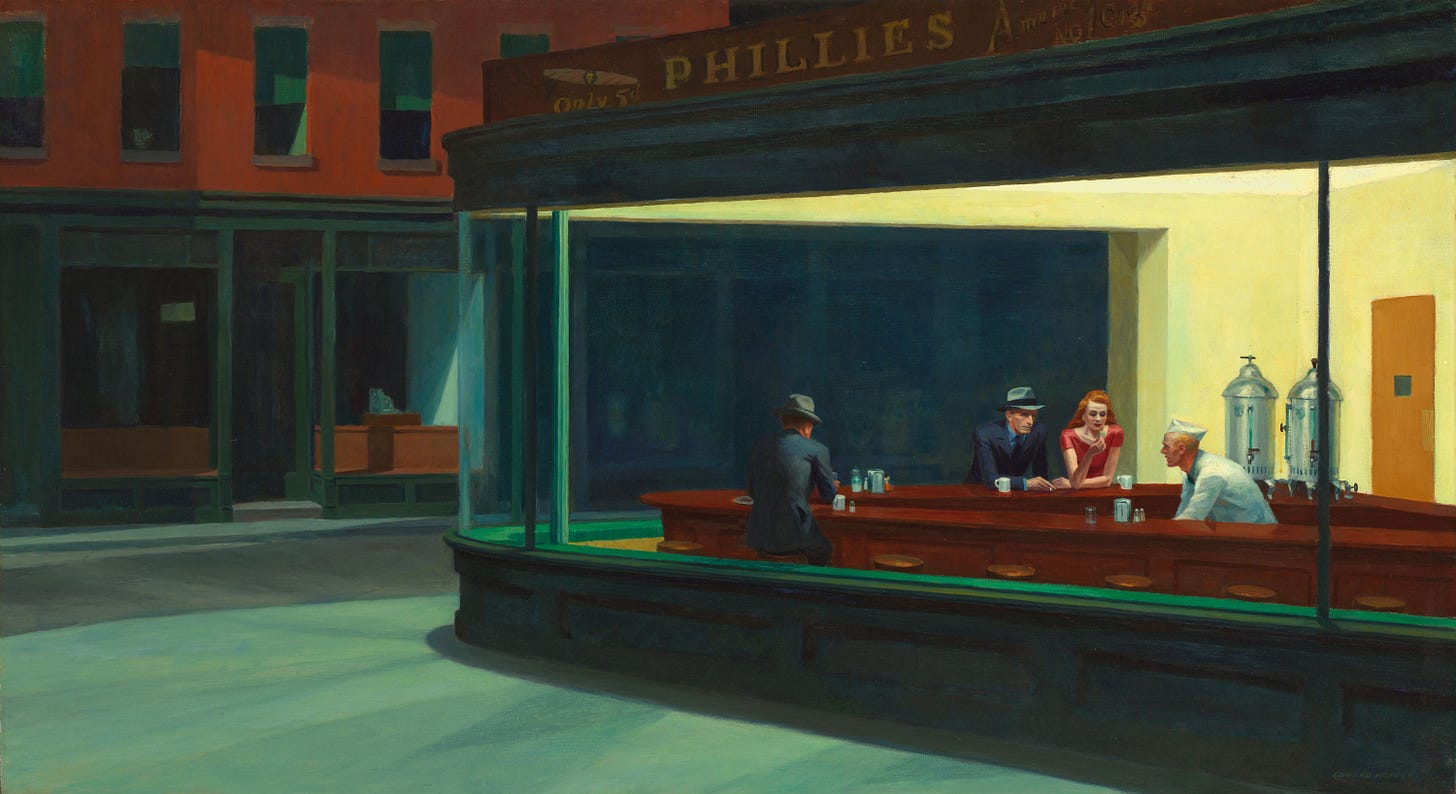

When I look at a work like Edward Hopper’s “Nighthawks,” there is no obvious message or statement to be found: instead I find a strange sense of mystery, a weird juxtaposition of liminality, loneliness, and beauty that is hard to describe but which feel familiar to me.

I get the same sense from Hopper’s “Morning Sun.” Is this loneliness? Despair? Is the warmth of the sun about to awaken her from this melancholy? Or is it somehow the cause, the warmth of it’s touch making her long for something else? Is the emptiness on her face, reflected in the sparseness of the composition, connected to the industrial landscape that clouds her view? Is Hopper suggesting that these emotions are the result of the modernist environment that was reaching maturity in the 1950s? I don’t know, but he captures here a feeling I recognize. And in recognizing that feeling, I feel connected not just to the painting but beyond that to the human expressing it through the painting.

Now compare “Morning Sun” to these images created by Karl Largerfeld for a 2010 campaign for the fashion brand Fendi.

There is certainly a necessary level of artistic skill needed to craft and style these images. But unlike Hopper’s original work, there is no mystery at their core. We do not need to wonder what the images are trying to expressed, what the model is feeling, or what emotion the photographer was trying to convey.

We know the purpose of the image is to showcase the clothes, to get us to associate these clothes with the prestige of Hopper’s art. The images are trying to get us to buy something.

While I like these images, and think Largerfeld is obviously a talented photographer–Martel would argue, and I’d agree that they are not art but works of artifice.

Artifice isn’t made for the purpose of exploring some deep mysterious feeling. Artifice might use or evoke feelings but it’s ultimate purpose is to convey information, or to get the viewer to do something, whether that’s drinking a Pepsi, or yielding to oncoming traffic.

And doing this can be important. You do not want a stop sign to express the profound mysteries of the universe: you want it to clearly and effectively convince the viewer to take an action.

Authentic art, by contrast, takes us out of the realm of the utilitarian altogether. According to Martel it “astonishes and is born of astonishment….”

“Astonishment is the litmus test of art, the sign by which we know we have been magicked out of practical and utilitarian enterprises to confront the bottomless dream of life in sensible form”

In this view art is made and exists simply and as an expression of and way to encounter the mystery of life.

And the astonishment that defines art can come in the form of a grand expression of religious wonder, or a more subdued examination of subtle emotion. Or it can come in something as small as attention to the way light plays across curtains blowing in the wind, the simple beauty of how objects and color dance together in a room, or even a self aware study of the way large expanses of tone and the texture of brush strokes can evoke a certain emotional states.

Martel argues that this astonishment comes not from transcending the uncanny strangeness and mystery of our very everyday existence, but by awakening us to it.

Astonishment is not necessarily a conscious end goal that the artist sets out to symbolize within the work–it is the driving motivation, something that comes through the process of creating the art itself, revealed both consciously and unconsciously in the thousands of decisions made by the artist in the act of crafting the work.

Each culture or individual has their own taste in what they value and a stylistic language they use for expressing this astonishment. What astonishes one person or culture may confuse or bore another. But what all art has in common is this attempt at expressing our own astonishment at some aspect of existence itself.

And while not every work of art will awaken this astonishment in every viewer, when art is serving it’s true purpose, astonishment is there.

AI Cannot Be Astonished.

I do not really know if the painters in Chauvet were expressing a sense of wonder, fear, desire, worship, or celebration in their depictions of the animals that would have been their source of life. Perhaps what lead them to create these images was the way all these complex feelings about the subject coexisted within them. We can only speculate.

What I do know is that there was something astonishing in these painters experience that drove them to take time away from all the activities in their lives that served an explicit survival function, to engage in the act of expression.

Whether or not we get our interpretation of these images right, much of the value we get out of looking at these works comes from trying to connect with what they were expressing.

So what happens when we have an AI create cave paintings, or any other kind of image that looks like art? It might be visually similar, just like an advertisement might bear a resemblance to a work of art, but as an image object I would argue the AI generated image does not carry the expression of life that true works of art do.

AI, unlike the cave painters and other artists cannot “express” astonishment at some aspect of life through art, because it is not itself experiencing that life, it is not feeling the astonishment to then translate into the artistic process.

Anything it makes can only be an imitation of how a human expressed a part of life. An imitation made with no understanding of what it is imitating, or why.

You can ask an AI to generate an image of what loneliness and alienation looked like in the 1950s. And you might even resonate with AI’s depiction of those feelings in some way. But these images are not an actual artifact that reflects the real human emotions that someone felt in 1950–while Hopper’s painting are.

And I think the extent to which we might connect with the emotion of an AI image is simply the extent to which we connect with its ability to imitate of how human artists have already translated those experiences into art.

It can generate infinite variations of these imitations, in every conceivable style, but it cannot add to the corpus of art something new born out of a direct contact with existence. It does not have it’s own experience of loneliness to express.

What draws me to a Hopper painting is not the content of the images themselves, but what is behind them. A painting is not just wallpaper meant to decorate a room. I do not look at his work just to see a city street or a woman sitting in a bed.

What draws me to Hopper is his perspective on these scenes, the way he captures certain feelings through how he constructs and paints the everyday. He saw the world in a certain and expresses that perspective through his work, his work of art connects me with another human’s experience, while the artifice only connects me with the arbitrary elements of style that Hopper used to communicate his experience.

I believe much of what draws us to art is the artist’s perspective, literally getting to see how their way of seeing the world is encoded into their work.

AI fundamentally, does not have its own perspective on the world. There is no way of seeing to encode. At least in its current iteration it can only produce imitation of existing perspectives. That might work for the creation of artifice, but leaves out one of the most significant reasons we are drawn to art.

Data and Consensus.

The heart of this issue is not just found by evaluating the end results, it’s also found in looking at how the works are made.

The artifice of AI generated images or text is baked into the very way it is created. Beyond conveying information and commands, Martel argues that artifice works in service of creating consensus:

“Consensus is the statistical world of useful knowledge, generalization, habit, custom, and ideology. Works of artifice reinforce Consensus by representing reality as though everything had already been mapped out.”

The Machine Learning Algorithms that generate text and images, literally work by using statistical and mathematical analysis to try to create predictive data. An AI generated work is not created using the artistic process: it is created by visualizing consensus found in data and information.

AI uses this consensus to reverse engineer an image in order to meet the desire or expectation we give it through the prompt. The AI image is a visual expression of the very consensus that Martel argues is antithetical to art.

While we might use it to generate something new—in the sense that it might be a particular arrangement of pixels or words that has never existed before—it seems to me AI cannot be a means by which true astonishment and mystery are captured and transmitted because true astonishment and mystery are not pieces of data or information: they are something strange, felt and experienced.

In this sense, true art is the part of life that cannot be turned into data or information, that’s the whole reason why we encode these things into poems, paintings or songs, in the first place instead of just describing them using logic and reason.

But why care?

Why should we care so much about this distinction between Art and Artifice? Because if we lose sight of the distinction we risk becoming victim of two unfortunate misunderstandings:

First, we might treat works of art as artifice and lose out on allowing ourselves to experience the astonishment and connection that authentic art has to offer.

Or we believe that works of artifice is are works of art, and leave ourselves vulnerable and exposed to the ways Artifice is trying to influence our thinking and behavior.

Our society currently is in the grips of both misunderstandings, beyond the ways we’re manipulated by advertising, we fall prey to all manner of propaganda.

And we simultaneously devalue the power of art by frequently asserting that everything is artifice, that there is no room for something greater that can truly move us profoundly.

Martel argues that in our modern world we are often closed off to allowing the forces of art to profoundly effect us as a defense mechanism against the manipulative power of Artifice. That the very guardedness that we use to protect our mental health in such an artifice saturated world, has turned into an apathy toward art.

We put on ironic detachment, and see being unaffected by authentic expression as cool while we view those who can be moved as weak. Sentimental and romantic becoming insults.

The jadedness has affected the artists themselves, who often only engage with anything sincere through a layer of detachment, not wanting to be seen as cliche.

The cost of all of this is high: cynical artifice posing as art, concerned only with its own commercial viability, and numbed-out audiences unable to connect with the artists and works that manage to get past the cynicism and exist as works of authentic art.

Not Just Another Tool.

I’ve focused here mostly on images generated entirely by AI. But what if AI is just one small tool used in the process of making a larger work of art?

I don’t think any small piece of artifice within the larger work necessarily corrupts the entire thing. I do not think just because a small amount of AI was used on part of Adrien Brody’s performance in The Brutalist that the entire film has no artistic merit and needs to be called Artifice. There is obviously a big gap between that and Tilly Norwood becoming a reality. And all art that exists within a capitalist marketplace necessarily has to negotiate a relationship with the forces of artifice to be produced and seen. I am not proposing a strict binary.

And perhaps–as Jason Blum suggests—if we can iron out the ethical and legal issues—AI might find a place as another tool in our toolbox, like CGI or digital cameras. But I think we should be very hesitant to adopt it without serious consideration about what it does to the artistic process.

Because what makes art a work of art is not just the end result but the process we use to get there. True expression in art emerges from every tiny choice made in the process of bringing that art into reality as a representation of our experience and perspective.

The artistic process is something both conscious and unconscious that reveals itself through each brushstroke, through accidents and how we respond to them, through collaborative decisions made by humans, through the way the environment we make the art within subtly influences each choice in that process. Each decision or accident we make in the process of creating art is an opportunity for meaning, perspective, and experience to sneak into the work, even when we’re not consciously planning for that to happen.

Any aspect of the process that you use AI for necessarily removes you from the process. But you and your perspective is the very source of what makes something art. The “prompt” is not a tool you express yourself through but a way of describing an outcome you want to achieve and having something else try to achieve that for you. If the essence of a work of art is often found in the very process of attempting to get to an outcome, AI disconnects us from that process.

In the documentary series Mr. Scorsese, Leonardo DiCaprio shares a story from the making of The Aviator, in one scene after many takes both he and Scorsese new that something wasn’t working. And eventually Scorsese told him it wasn’t working, but did not tell him what to do to make it work, because Scorsese knew it would be more valuable, and more authentic if DiCaprio found what worked on his own.

Scorsese did this because as an artist he knows that the process matters, and that even when working with a human, giving them an explicit outcome to work towards can sometimes be antithetical to the artistic process.

So if we want the machine to make our art for us, it strikes me that we may not understand the purpose of the art we’re making. That the true value of art is not in the perfect outcome that we imagine AI will help us achieve, but the process we take to get there. And when we use AI we risk undermining the very process that allows deeper meaning to emerge through our work.

A typewriter might have made writing words more efficient, but it did not write the words for you.

If you want to make true art rather than artifice, you must engage in the artistic process not to have a perfect, finished work that makes your experience comprehensible, but to have a work that brings the audience along on your attempt to express incomprehensible.

This is why looking more closely at a work of art reveals deeper meaning, while looking closer at a work of Artifice often reveals it to be less meaningful than it originally seemed.

Yet I Am Astonished.

But I must admit: while I have not yet encountered an individual AI image that feels like a true work of art, I sometimes do feel a kind of dreadful astonishment at what these images represent.

If we peer into this endless hall of mirrors constructed to reflecting everything we’ve ever created back at us and ask why? What do we see?

When I look at the whole of AI generated images this way I see a work that astonishes me with it’s absurdity, surrealism, emptiness and glut. An attempt to create a work that encompasses everything humanity has created while simultaneously trying to remove as much of ourselves from the creative process as we possibly can.

I see humanity trying to abandon its own involvement in the act of creation, leaving itself with only its desires, its prompts waiting to be filled with increasing accuracy, precision, and speed.

And I wonder if maybe this attempt reveals a hidden desire for self-negation.

That perhaps our desire to remove ourselves from the creative process itself is born out of a belief that we are fundamentally flawed, and that we must overcome those flaws by creating a machine that transcends our imperfect abilities.

One that can infinitely meet our needs with the touch of a button, without ourselves or another human being needing to be involved. That can put an end to the unbearable mystery of it all.

But what if we have it backwards?

What if our involvement in the process, as flawed as it may be, is the very thing we desire and are trying to satisfy with this endless cascade of novelty, information and increasing productivity?

What if what we are seeking a machine that can perfectly fill our prompts, when what we truly desire is for ourselves to be prompted by our own artistic vision: to care enough about something, an experience or perspective on the world that we want to do the creative labor ourselves, to falter through the decisions, finding the expression of the beauty in each brush stroke.

What if what we want is an artistic project where no shortcut is fulfilling because the project is not a means to an end, but fulfilling as a process in and of itself, a part of life, which is not a problem to be solved, but a mystery to be astonished by?

Imagine that perhaps 30,000 years ago the cave painters finished their work, put down their torches and charcoal, gathered around a fire together afterwards and one of them said “wouldn’t it be great if we could create something that would do the painting for us so we did not have to do it ourselves?”

In the interview where Jason Blum said the industry needs to embrace AI, he said “The consumer does not care if what they’re looking at is AI.” And at first I thought: he’s wrong. Some people, like myself, do care about whether or not what they’re seeing is AI. But looking closer I think he’s right. A consumer does not care about whether or not what they’re seeing is AI—a consumer is just looking for whatever might be available to fill the craving they have in that moment. Whatever might draw them in, appease, and amuse them will do the job. And there is money to be made giving consumers what they want.

But are we here just to consume? Or do we want something else?

Appeasing consumers is not the purpose of a work of art. If you are creating to appease, or experiencing something for the sake of being appeased you are within in the realm of artifice.

Art is made not for consumption but for the sake of expression, connecting with yourself, others, or existence itself through that expression.

While there is a place in this world for the creation and consumption of artifice, if we lose sight of the role that art can play in our lives, both as artists and as audiences, we lose sight of a valuable part of being human.

We cannot escape our desire for the connection provided by authentic art by getting better, faster, and more efficient at making artifice.

I had an art (drawing) teacher who made me go outside and find a stick, the cruder the better. Then she said okay, now draw this flower -- incredibly delicate and complex -- using just the stick and india ink. It was impossible. That was the point. She wanted me to *create* something, not attempt to replicate a photograph. My cognitive dissonance nearly brought me to tears. In the end, though, I liked what I drew, including the long drip of ink running crookedly down the paper. It was messy and crude, yet somehow an essence of the flower came through. The process of doing, and feeling, is essential.

That experience was more than a foundational lesson, it was an epiphany. It changed how I *see*. In a million years AI could never replicate or even poorly mimic the indefinable human connection, or essence, of this drawing. As you said, it's the human process that instills art with that visceral something that we all immediately recognize and resonate with (even if we can't adequately define it).

In 1903 James Joyce defined art as "the human disposition of [...] matter for an aesthetic end", i.e. created by someone consciously manipulating materials solely to create beauty. It's a straightforward, seemingly bulletproof definition—except Joyce then defines photography (a non-human disposition of matter) and furniture (which exists for practical, not only aesthetic, ends) as not being art.

Most efforts to definitionally exclude AI from being considered "art" get tied into the same knots, a problem I feel your approach of emphasising intentionality and process helps sidestep, focusing not on a narrow technical definition but on the experience of creating and engaging with beauty. I don't agree with every point (I can accept some forms of artifice/advertising as falling under the "art" umbrella), but it echoes my own objection to AI "art"—that the pleasure of art exists in the challenge I have to do in expressing ideas beautifully or making sense of them in someone else's creation, and taking the difficulty out of it takes away the pleasure.