David Lynch changed TV, Film, and How I Think About Art Forever

David Lynch leaves this earth at age 78.

“Cinema is a language. It can say things—big, abstract things. And I love that about it. I’m not always good with words. Some people are poets and have a beautiful way of saying things with words. But cinema is its own language. And with it you can say so many things, because you’ve got time and sequences. …And you can express a feeling and a thought that can’t be conveyed any other way. It’s a magical medium.” -David Lynch, Catching the Big Fish

Loss can suddenly bring into sharp relief just how significant something or someone was to you. David Lynch was not just a director whose work had a profound influence on me, he was a significant force in expanding, shaping, and directing my understanding of cinema as art, of what art could be, and of art as a spiritual practice.

David Lynch was also a familiar face. Twin Peaks was the first TV show my wife and I watched together. The first show we binged together while curled up on the couch, and to this day the only show we’ve watched together multiple times. I didn’t know who he was when I first watched the show, but Lynch’s absurdist performance as the hard-of-hearing Gordon Cole somehow conveyed the genial warmth I would come to later associate with the man himself. My love of the bizarre, irresistible world of Twin Peaks led me down a path of discovery that would forever change my view of what film could be.

For many people I know, Lynch’s films were a key doorway from mainstream cinema into the world of the genuinely strange and avant-garde. At the time I first watched Eraserhead, his debut film, I had truly never seen a movie that strange. I had no idea what to make of it. I hadn’t realized there were people out there making movies that weird (ah the innocence of youth) but I was hooked. I now know that Eraserhead is just the tip of an iceberg, but I mean that as a compliment. It was an introduction to an entire world of film that I now love. But the film’s director didn’t just make the movie that introduced me to that world, he helped me get comfortable there. The way he spoke about his films, and art more generally helped me realize that art could explore a realm beyond what my thinking intellect could comprehend.

It was Lynch who helped me understand that art didn’t need to be explainable. That I didn’t need to understand it. That it wasn’t the artist’s job to speak for their work, but through it. His refusal to explain his art wasn’t just a rebellion against the industrial-interpretive-complex, it was an artistic philosophy. An affirmation that the value of the experience of the art was itself enough. That there was something contained within that experience that did not need to be explicated.

Being exposed to these ideas through how he talked about art in interviews and in his book Catching The Big Fish, didn’t just help me better understand his movies; it introduced me to what art could be. Because of David Lynch, I understand and appreciate all art more deeply.

Lynch isn’t the only one who talks about art in this way. I’ve since been exposed to a whole world that talks and thinks about art through this lens, but for me, he was the gateway, and I think the frank attitude with which he conveyed these ideas made them tangible and accessible. For someone as deep into the strange and avant-garde as he was he had an utter lack of pretense about it that is incredibly rare.

Lynch hasn’t just influenced me personally. His work has had a tangible effect on the world that is probably much larger than most people realize or he gets credit for. Twin Peaks, which aired in 1990 while it was slow to be received by audiences at the time, revolutionized TV. It was the first television show to explore a single murder case across an entire season, helping pave the way for the shift from episodes as contained stories to chapters in a larger narrative, the format that birthed the “golden age” of television. The show pushed other boundaries as well. It was deeply strange and surreal for TV at that time, something which is much more commonplace now. It was more interested in the world it was building than the mystery being solved. It’s often cited by TV showrunners today as an influence, and many of the most significant shows of the last few decades (like The Sopranos and Atlanta) were heavily influenced by Twin Peaks. Even if you haven’t seen Twin Peaks, you’ve seen a show that exists because of the path that Twin Peaks forged for TV.

Twin Peaks: The Return, the third season that came decades later, is still, in my opinion, the pinnacle of avant-garde TV. I’d argue any day that the boundary-pushing eighth episode still holds the spot as the single strangest, most unconventional piece of television to ever air.

All this strangeness and the bizarre absurdity of Lynch’s work wasn’t just weirdness for weirdness's sake though. It wasn’t mere provocation. It had a purpose. While Lynch never spoke for his work and refused to explain what it was or what it meant, he wasn’t secretive about where his ideas came from or the process he used to make his art. Art, for Lynch, was a spiritual practice. It was a way of bringing to life ideas he found in an unconscious realm. In Catching The Big Fish, his book on the artistic process, Lynch describes how ideas are like fish: Little ones swim on the surface of our consciousness, and big ones swim in the expanse down below. The process was to dive into this realm, to find these ideas, and then to bring them to life. The artistic process for Lynch is a means of tapping into something much bigger than himself, something beyond language. The results of his process may not always be comprehensible to our rational mind, they may not lend themselves to clear interpretation, but they were created with intention, and always came from something or somewhere.

You can see it in his films. They often feel like waking dreams—narratives created by a recognizable mind, but which operate in a world not quite like the one we walk through in our waking life. Like dreams these movies often seem like they’re getting at something; forms and symbols trying to tell us something. They were acts of de-sublimation, uncovering the darkness hidden underneath the repressed world of 1950s suburbia in Blue Velvet, or the nightmares hidden in the back alleys of Los Angeles that we see in Mulholland Drive and Inland Empire. The films are revelations. You walk out of them like you wake up from a dream; knowing it means something but forced to feel through what it means in the absence of an easily identifiable rational explanation. Lynch was working out his fears, his darkness, and bringing it to life with such richness in these films that they allow us to explore our own. And he did this through his art so lovingly that it didn’t feel like he was trying to scare us or horrify us, but instead, like he was a parent talking a child through their bad dream. When we hide from our fears we hide from parts of ourselves. Art like Lynch’s can create a safe container where we can recognize those parts of ourselves and come to terms with their existence.

Lynch was never shy about the method he used to dive into this subconscious world. He was a vocal proponent of Transcendental Meditation, which he practiced religiously twice a day. TM garners some controversy for the somewhat expensive one-time fee that’s charged by its official teachers, but the reality is it’s just one kind of meditation practice that works particularly well for some people. I’ve never officially practiced TM itself, so I can’t speak for that method, but Lynch’s advocacy for the value of meditation was part of what inspired me to start my journey into mindfulness, one of the most beneficial things I’ve ever taken up. And I’ve experienced many of the benefits he’s talked about through my own practices.

But I think TM was just the tool David Lynch favored for diving into that subconscious realm to catch the big fish. He promoted it because it’s what worked for him, but I think there are many ways people access that realm. Sometimes it’s done through specific practices, sometimes it happens intuitively without trying. Rick Rubin’s popular recent book, The Creative Act, explores many of the same ideas from a slightly different perspective and with slightly different language. Lynch’s commitment to this approach in his artistic practice is, I think, I big part of what made is work so fascinating, bold, evocative, and influential.

I’m not sure all art must function as a revelation of the subconscious, though I’m suspicious that perhaps all art that resonates with an audience does on some level. But I am sure that one of the functions of the artist is to proceed into the realm of the unknown. The artist must explore beyond convention, boundary, and expectation. The artist cannot simply operate in the realm of the understood, the explainable, and the quantifiable. They must fearlessly venture out beyond these things and bring some of what they find to the surface. When they do this successfully their work will resonate with someone, somewhere, deeply. It will help us get in touch with what we haven’t yet named, understood, or quantified. It will give a voice to some aspects of our experience which was previously silent. And it will pave the way for future artists to explore the same path more fully and deeply.

This, I believe, is what David Lynch dedicated his life to by living what he called “The Art Life.” This is the legacy of Lynch’s work. The man is no longer with us in body, but what he mined from the depths of pure consciousness remains with us, living on through his art. And the generosity of his artistic spirit, to confidently go places with his work that few were willing to go, helped pave a new road for TV and Film that now is becoming well-worn by all those who follow his example.

It’s a beautiful thing.

Some Recommendations:

If you want to watch his movies I’m sure you know where to find those. Eraserhead and Blue Velvet are my personal favorites. But want to leave you with a few of my favorite pieces of David Lynch ephemera, the stuff that takes you beyond his work and helps you understand the man himself.

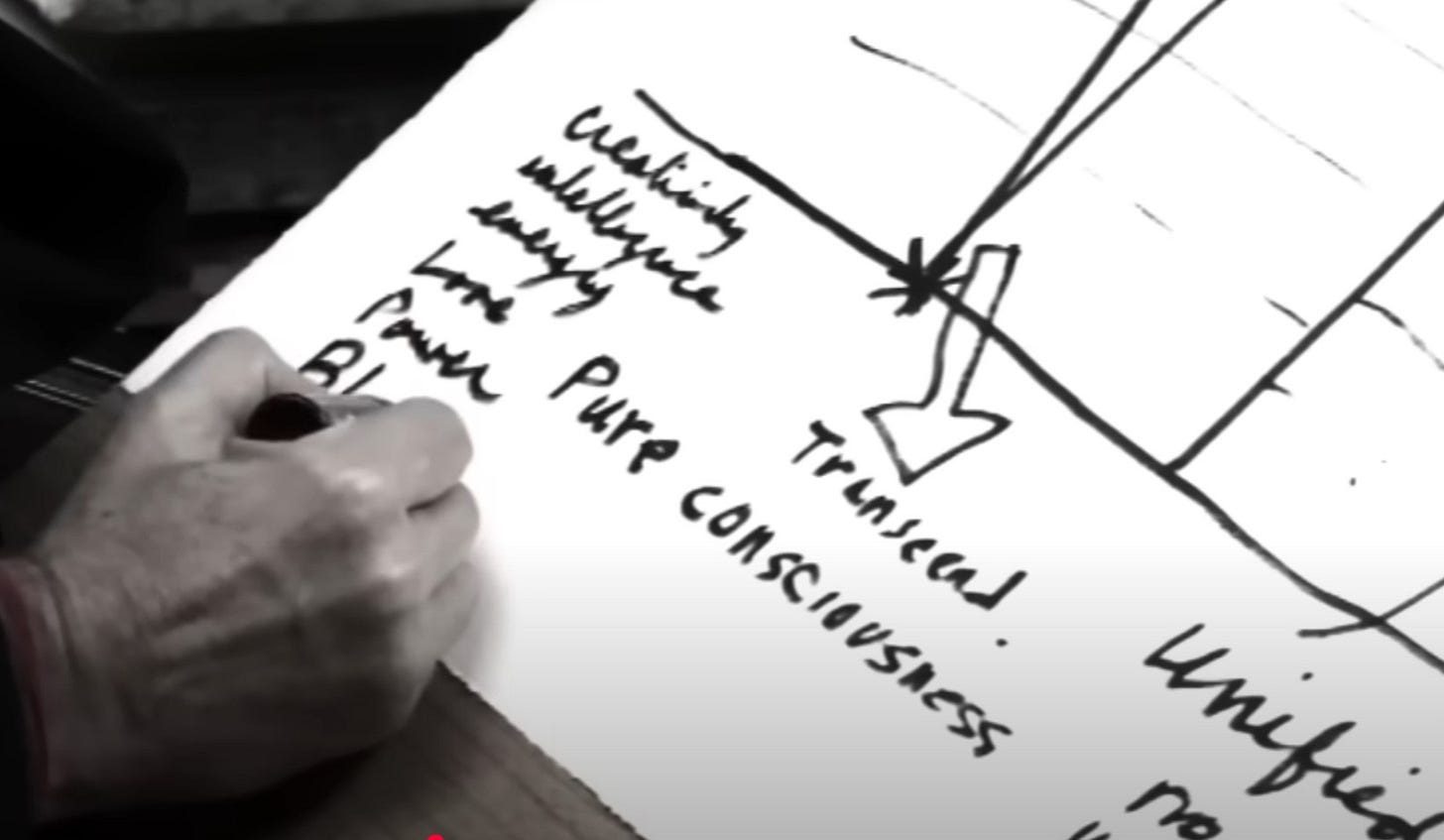

This video where he explains meditation and creativity is worth a look. It’s pretty esoteric, but there are some core ideas here that I think are a really useful framework for thinking about life and art.

David Lynch on cooking Quinoa. More than just a quinoa recipe, this 19-minute short from the bonus features of Inland Empire showcases Lynch’s remarkable capability to be captivating as a storyteller.

The Story of a Small Bug. Just Lynch telling us about a bug he found in his backyard. May we all see the mundane world with this level of wonder and grandiosity.

This interview for the BAFTA. Lots of great tidbits, including the famous response to being asked to elaborate on the statement “Eraserhead is my most spiritual film.”

An artist who truly transcended in the film industry. Forever a legend. 🕊️

he’s the embodiment of art